Time to Get Even More Freaked Out About AI with "Eliza"

anyone else getting real annoyed with AI summaries and assistants being crammed into everything?

I've been putting off this article for a while because I am so, so tired of generative AI. I will never shut up about how angry generative AI makes me. I'm seeing it everywhere. Students, friends, and family members started not only using it, but treating it as anything from a fun little diversion to the sole necessary tool to accomplish a task for work or school. I have been furiously following the tales of authors who forget to take AI prompt instructions out of published novel drafts, sometimes with explicit instructions to copy the styles of other authors. I've even gone back to using two en-dashes instead of collapsing them into a single em-dash to preempt any thoughts that I use AI to create or edit my work. I promise you, my soul will leave my body via spectral woodchipper before I cede my ability to write for myself.

All that to say: I'm probably the perfect target for Eliza, which came out in 2019 from programmatic puzzle game dev Zachtronics. Eliza is a narrative-heavy visual novel with about 6 hours of linear story and no branching paths until the ending. I first played it in probably early 2020 and it got wedged into the crevices of my brain alongside everything else that went terribly that year. But at the time, it read as a cautionary scifi tale that leaned toward the exaggerated, maybe even alarmist. I'm sorry to say that playing it again in 2025 is extremely spooky and might still serve as roadmap to all the ways AI, particularly generative AI used for companionship and mental health, have plenty of room left to grow and hurt us.

Content warnings

Here's what you're in for with Eliza:

Eliza follows someone who works for a mental health chatbot, putting her in contact with people who are struggling with their lives. Be prepared for discussion of serious burnout, professional jealousy, debt, existential pain and dread exacerbated by advances in technology, disordered relationships with alcohol, technological invasion of privacy (think of a coworker going through your phone), and the offscreen/discussed death of a professional colleague. There are also no-details-given mentions of sexual misconduct by a superior, a fractured family relationship, and light pressure to return to a difficult work environment.

Narrative hardware

Setting

Eliza is comfortably set in a 20-minutes-into-the-future version of Seattle, Washington. Background characters can be seen wearing Seahawks merch, and protagonist Evelyn goes to visit the Puget Sound late in the game. The Pacific Northwest vibes are immaculate: characters typically wear layers to combat the weather, which is usually somewhere in the foggy-to-drizzly spectrum. We get precious few views of nature, though--more on that later.

The first ten

Right away, you'll notice that the game is fully voiced. Evelyn Ishino-Aubrey, our protagonist, gives us a few cryptic lines about having had a dream, but forgetting it when her alarm went off.

We catch up with her on the light rail in Seattle, thinking during her commute to the first day of her new job. While her spoken lines are voiced, her internal thoughts aren't, leaving us to imagine her tone as she looks around the light rail car. She can check her phone, but she doesn't seem to have many (or any?) contacts to chat with. The only things of note in her email inbox are a nagging reminder from her lapsed gym membership, an onboarding email, and an affirmation from herself: "You will do it. I believe in you."

Evelyn meets with her new supervisor Rae, who walks her through the office and helps her get situated in her new job. It's here that the titular Eliza comes into play: Evelyn is working as an Eliza "provider proxy" in a counseling center. As one of her onboarding messages reminds her: "Keep in mind that you are present only in order to provide the human touch to an interaction that is fundamentally between the client and Eliza." A provider proxy is just that: a human proxy that delivers Eliza's AI-driven lines to the client from a human being. (To be clear: As far as I can confirm, nothing in Eliza the game was actually made with generative AI. The story is about AI, but was written by humans.) Evelyn's job is to be a calming presence as she plays the role of therapist for Eliza's clients.

Ahead of her first session, she sits in the counseling room and muses about how truly therapist-office the space feels. "Was this how I imagined it working?" she wonders to herself. "I can't remember anymore. The future happened without me."

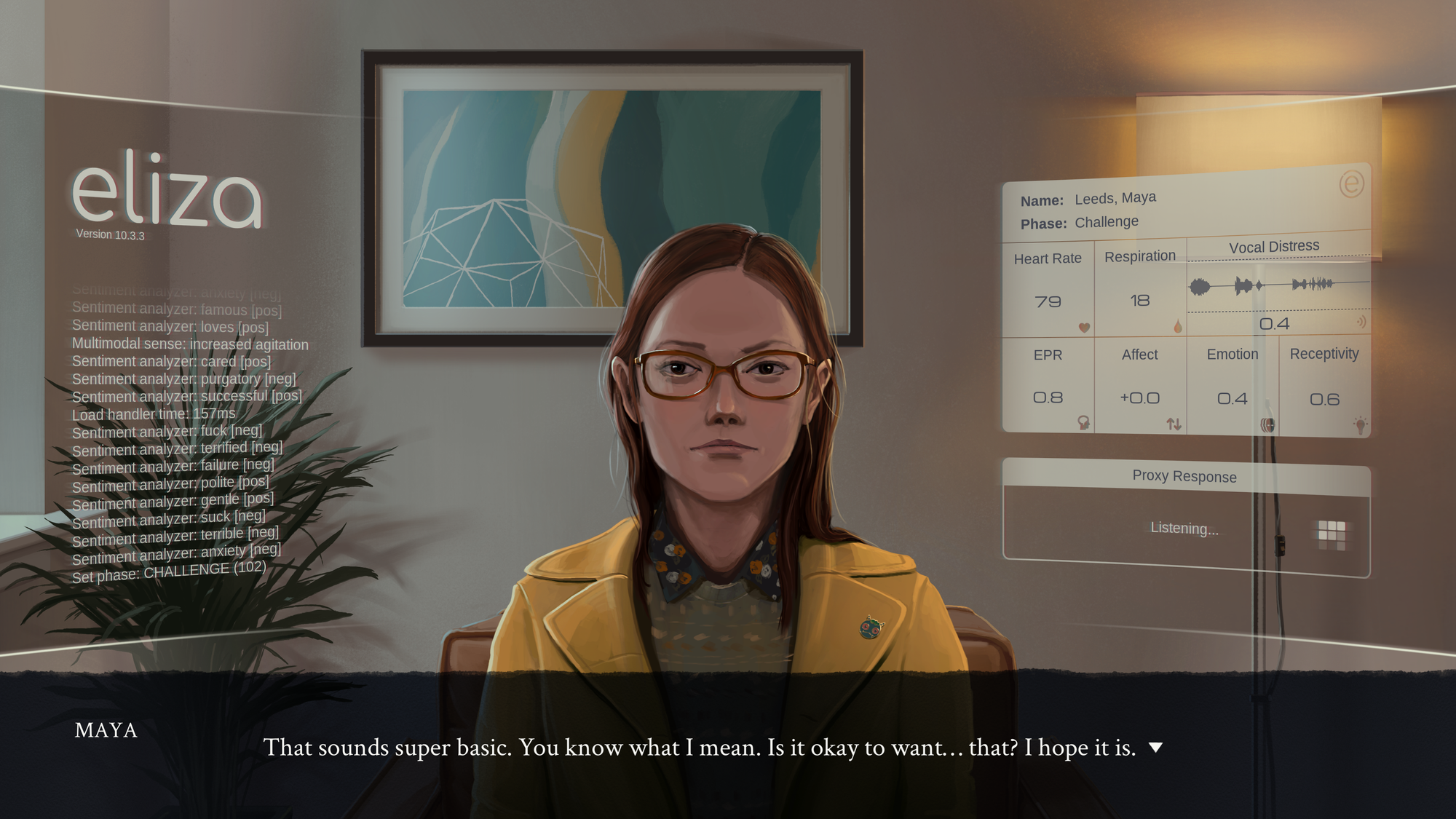

Her Eliza headset boots up, giving her a HUD over her view of the therapy room and her client. Eliza version 10.3.3 provides a wealth of information about the client, including his name, notes about his vitals, and a dedicated box for "Proxy Response." Evelyn's job as a proxy is to read lines generated by Eliza's therapy AI in this response box.

The first client is named Darren, and he takes relatively little prompting before coming out swinging with the existential dread and emptiness. Taking note of the headset HUD's many sections, you can get a sense of what Eliza is considering in his responses: it picks up keywords like "hollow" and "cruel" when he says them, and analyzes his speech patterns for "vocal distress" as he explains why he sought out an Eliza appointment. All this suggests that Eliza is performing sentiment analysis in real time as part of its psychological profile of the client. This strikes me as a rather blunt-force approach to therapy, but Eliza is clearly working hard behind the scenes to develop a care plan. Evelyn's job is to trust the machine to do that hard work for her.

Darren freely identifies his biggest problem: feeling disconnected from others. He wonders what the point of humanity is when all around him, he sees greed, irreversible environmental damage, and the cruelty of people who just don't seem to notice or care about it. He says that he wishes he could "have some actual communication" and talk to people, which he uses as a springboard to beg Evelyn herself to speak to him without the AI.

And Eliza prompts her to respond as if she has: "Ok. Hi, Darren."

Evelyn's session with Darren in a calm office setting. Left: Darren says, "Look, I'm desperate and I can't even talk to a real human being!" as Eliza's "Proxy Response" box reads "Listening..." Right: Evelyn replies with lines directly from Eliza's "Proxy Response" box, which reads, "Darren, I'm going to get in trouble if I deviate from Eliza for too long."

Eliza prompts Evelyn to give Darren her name (which feels like it should be some sort of AI-driven violation of a HIPAA-adjacent law), then moves swiftly on once Darren calms down. "I'm not used to people doing things for me," he says. Eliza then launches into the Intervention phase of the session, in which it prescribes breathing exercises for calming overwhelming moments, and suggests he talk to his doctor (presumably a real doctor) about a specific medication, which it believes "might help you feel better." Eliza concludes the appointment with "We hope to see you back soon."

Darren gets up and leaves, and Evelyn's headset moves on to a results screen, which shows that Darren neither rated her nor left her a tip--but she did level up! We don't get direct confirmation of Evelyn's actual wages, and the potential for Eliza proxies to work solely on a tipped wage adds a sinister, dystopic seethe to the whole thing. What's the point of a tipped wage in a job where Evelyn can't be herself? Whose fault is it if the client doesn't leave a tip? If she doesn't get a rating, is that more Eliza's fault than hers? Isn't the point that Evelyn is merely the vessel for Eliza's speech and actions?

Evelyn checks back in with Rae after the session ends, and Rae listens back to the session (which feels like another violation of some kind, but Rae assures us she has "privacy clearance," so everything is definitely fine and above board). She comments that they've gotten enough of "these guys" that Eliza now has a built-in script to respond to demands to speak to a real person. Evelyn muses that she would never have thought to create such a feature, but stays focused on Darren. Will he be ok? She asks if Eliza can refer clients to more acute care, which Rae kicks back to the disclaimer given to clients before every session: if their problems are really serious, Eliza isn't qualified to address them. Ta-da! No liability!

If it sounds like I'm characterizing Rae a little unfairly, I admit that I am. Rae is extremely excited about this technology (she runs three Eliza counseling centers), so she's more motivated than most to see it run well and watch it succeed. Evelyn has a more even-handed approach, remarking on the technology's effect on the clients and whether or not Eliza is making a tangible difference in their mental health. This is a counseling center, after all. Shouldn't we want the best for our clients?

The first chapter

So, as Rae has just reminded us for liability reasons, it's important to remember that Eliza proxies are not real, licensed therapists and do not provide actual mental healthcare. While many proxies are tempted off-script by a natural human inclination to help people in distress, she points out that Eliza works because it evaluates client problems from "a neutral perspective" that humans aren't capable of. To think of it this way, Eliza's inherent distance from human life would give it the ability to analyze and solve human problems in ways humans might not (or might not be able to) consider. The proxy's job is to give that perspective a human face and a warmer touch than just reading lines off a screen.

The unavoidable overlap of Evelyn's personal life with her work unfolds slowly, like much of this game. After her first session with Darren, she gets an email from "The Damien Seabrook Memorial Fund," announcing three organizations the fund plans to support in the coming year. These include an NPO focused on making modern mental health accessible to all, a tech-industry-focused organization fighting against exploitative working conditions, and a foundation for humanitarian open source software.

After another, more typical session with a woman named Maya, Evelyn gets to call it quits for the day. She meets up with an old friend named Nora, who has completely reinvented herself as an underground musician. The granules of their past friendship come slowly: they were work pals at a tech company. Nora is somewhat surprised to hear that Evelyn is working as an Eliza proxy, wondering if "they know." Evelyn says she hasn't told anyone. Told anyone what?

An email from a culture journalist answers that question. "I'm trying to track down a certain Evelyn Ishino-Aubrey who was one of the principal developers of the 'Eliza' system from Skandha." Evelyn isn't just working for Eliza now... she was one of the coders who originally brought it into being.

Gameplay

Controls, accessibility, saving

Eliza works on a checkpoint system, which autosaves your progress at specific points in the narrative. The start menu offers a DVD-style "Chapter Select" menu, allowing you to hop around within the story once you've already completed it. Since some sections can run long, it's nice to be able to pinpoint the conversation or moment you'd like to revisit with more precision than the chapter itself.

Controls-wise, the game is a classic visual novel with some choice points to direct Evelyn in conversation with others. The pause menu allows you to tweak game options, including the auto-advance option (which comes in "normal" and "slower" speeds). There's also a dialogue history you can access while in the game if you need to refresh your memory about what's been said.

Left: Eliza's options menu, which allows tweaks to display settings, volume for effects, voices, and music, and text options. Right: An in-game look at the history, which shows a transcript of what you've read so far.

Tech is life

Every so often, Evelyn gets a break from conversation to just take in her surroundings. For example, she can check out the lobby of the Eliza counseling center she works at, or she can check her phone. Like many modern Americans, Evelyn is never without her smartphone, and she can even pull it out during conversations (though her friends tend not to mind as much as yours might). The nightmare rectangle is always within reach, but it acts more like a part of gameplay than a true pause mechanic. Her phone has a few games (most of which she won't open and says she needs to uninstall), her email, a social chat/IM app, and a work-related chat app. Eliza's sole Steam achievement is for beating the devilishly hard "Kabufuda Solitaire" game on Expert difficulty. I got to Hard Mode and had to cool it before I got too sucked in.

Left: A game of Kabufuda Solitaire in progress. Right: I won! It was on Easy, but I won!

Something else that stands out thanks to the softly warm art style is the lack of outdoor time. In the PNW, I would love to go out hiking or see some nature, devastating allergies be damned. But Evelyn is a city girl through and through, and so we never get to take in the outdoors except for a key moment when she tests her ex-Skandha supervisor Soren's startup, a company called Aponia. He's going straight for the brain with a different brand of high-tech mental healthcare than the Eliza counseling centers: Aponia is seeking R&D funding for induced dreaming as a means of reducing or even eliminating pain. Evelyn gets to test this technology during a one-on-one meeting with him, finding it momentarily pleasant but not yet perfect.

I find it significant that this is one of the only times in the game when we get to see nature and trees in full, lush color. Part of the issue is definitely that Eliza takes place during the winter, but I can't help but go back to Eliza's favorite intervention: VR experiences to calm the mind. It feels very much like Soren is also going all-in on a commodification of nature-as-wellness. If we package up the right feelings of breezes and sounds of birdsong, and if we enhance these sensations to literally bring the color and life back to your world, maybe we can remind you enough of the natural world that you won't actually need it. The undercurrent of technology supplanting or outright replacing parts of the world as we know it, thereby changing how we interact with it, runs deep in Eliza.

Left: Evelyn's test of Soren's "induced dreaming" technology takes her to a warm, beautiful place. Right: Evelyn admits to Soren that the experience isn't perfect: "But I didn't completely lose awareness of the real world. It was more like... a mental state that I was experiencing."

Therapy time

Each Eliza session comes with distinct phases delineated within the headset. A Chapter 2 message from Eliza's service director breaks them down:

- Introduction: Eliza builds rapport with the client alongside a "psychological state model." Proxies are asked to listen actively so as not to appear uninterested or disengaged.

- Discovery: Eliza addresses the client's problems with questions. Proxies are again asked to be attentive.

- Challenge: Eliza identifies "rationalization and/or explanatory strategies" in the client's thinking and encourages them to reevaluate. Proxies should be careful not to inflect their lines with an adversarial or confrontational tone.

- Intervention: Eliza offers breathing or mindfulness exercises in the Skandha Wellness App, and may also recommend prescription medication or discussing treatment with a doctor.

- Conclusion: Eliza asks the client to rate, leave a tip, etc. Proxies receive this feedback and tip on that results/level-up screen after each session.

I found the Eliza proxy sessions interesting, since each client has their own problems and come with their own mini-narratives that Evelyn only gets to see parts of. It puts me a little in mind of Spiritfarer, which showcases only snippets of each spirit's life--true to what a real-life hospice care worker might see. We only put parts of ourself on display for therapists. As an Eliza proxy and not a true therapist, this is doubly true for Evelyn: her clients might be speaking to Eliza through different proxies every session, meaning Eliza is the only one who gets to see all of what a given client puts forward for examination. Proxies are even more cut off from the process, putting even more distance between them and their clients.

Narrative software

Story

Eliza carries some tremendous depth that has only become more prescient as time since its initial release has passed. Conversations about ChatGPT, OpenAI, and other generative AI models are dominated by concerns about the impact of AI on a social level, its mental health uses, and the implications of use and over-use.

I like that Eliza centers Evelyn and how she's fallen out of step with the tech world. We learn that she quit her job and completely withdrew from social life after finding her colleague Damien dead in the office of an overwork-induced heart attack, which is a tremendously valid reason to vanish off the face of the earth for a while. It's not just about the AI--it can never be just about the technology because no technology is created in a vacuum. The people who created Eliza are variously profiting from, disillusioned with, trying to replicate, or trying to escape from this lightning-in-a-bottle technology that has already profoundly reshaped the world of the game.

Plus, instead of trying to tackle the behemoth of "AI itself as a technology," Eliza carves out a specific niche of AI to attack. AI-as-therapy is obviously an attractive prospect. Outsourcing difficult emotional labor, which must (ideally) be performed by trained and licensed professionals, to a robot who can do it for a fraction of the cost and with none of the drawbacks of human labor? Huge. Such a technology would not only lower the barrier of access for people who need help, but could open the doors for research and understanding on a massive scale. What if we could study the care of hundreds of thousands of patients? What if we could learn about how to make care plans better? Of course, we'd have to make sure that all that data collection is ethical. Right?

Data hunger: "Transparency Mode"

Soren brings up in his Chapter 2 startup pitch that Eliza counseling centers can also "pull from (the client's) digital life" in order to gain more data, which helps Eliza make a determination about counseling approaches. Evelyn later learns that some Eliza proxies are able to test this new "Transparency Mode" if a client gives permission. Once given, Eliza can access the client's personal messages, emails, etc.

Evelyn's experience with Transparency Mode is essentially an Eliza-generated reading comprehension test. Think grade-school-level SAT questions. She gets access to a curated handful of text threads and emails, and is then presented with three conclusions about the client based on the psychological profile Eliza builds.

The questions aren't really the interesting part. What's intriguing is the way the clients' personal data (which, counter to Skandha's pitch, is not anonymized in any way for the proxy) gives Evelyn another layer of insight about the client. My two favorite clients, Maya and Holiday, are the Transparency Mode testers in Evelyn's group of clients. Reading through their texts and emails offers information that doesn't come up in sessions. In therapy, Maya speaks to Eliza with a comedic self-deprecation, masking the full extent of her bitterness and how her self-hating tendencies affect her relationships. Holiday stands out in my memory as a client who just enjoys having a conversation with someone, but her Transparency Mode shows that she is struggling financially, and as an older person who isn't as tech-savvy as younger clients, she's not familiar enough with technology or available services to know where to turn next. Our third and final Transparency Mode participant doesn't actually volunteer. In a flagrant privacy violation, the Skandha CEO himself pushes access for Soren's profile to Evelyn, hoping that seeing Soren's dirty secrets will dissuade Evelyn from working with him again. But what's a privacy violation between ex-coworkers in a bitter rivalry, right?

I think it's telling that in his Aponia pitch, Soren goes on to point out:

"Collect as much [data] as you can, sure, but it's important to keep in mind that you can have all the data in the world and still not understand why things work the way they do."

For me, this is a critical point in Evelyn's skepticism about how well Eliza works as a therapy product. Eliza can draw conclusions--for example, by observing that unpaid bills notices means someone is in debt--but understanding the broader context of how these situations occur might doesn't necessarily translate to the power to do anything about it. There's an on-paper why for debt (whatever the reason, you didn't pay the bill), but the broader why of living on a fixed income, rising housing and grocery prices, the financial burden of chronic medical care, and any of myriad other potential factors presents only context without any actionable solutions. Eliza can't do anything about rent prices, but it can help you clear your mind so you can regain your lost productivity at work.

Pivot 1: "Coin-Operated Boy" - The Dresden Dolls

Have a listen/watch to "Coin-Operated Boy" by the Dresden Dolls, a song whose singer desires the titular Boy as a companion for all the benefits he offers over real, flesh-and-blood boys. He provides "Automatic joy / That is why I want / A coin operated boy / (...) Love without complications galore," and who wouldn't want that? Relationships with "All the other real ones / That I destroy" would take sacrifice and and an exchange of vulnerability--but not this one!

There's something attractive about the prospect of free loyalty. Intimacy without having to undergo the mortifying ordeal of being known. All highs, no lows. Such a miraculous Boy could successfully ape parts of a romantic relationship that we miss the most when it's gone: physical and sexual intimacy, attentiveness, loyal companionship--and all without the human partner ever having to put up any of the same. A Coin-Operated Boy that wants to be exclusive? Asks to meet your parents? Hates movies or foods or positions that you love? Non-starter. This Boy is not a relationship partner. He's a product that is designed to give you exactly what you want. Nothing more, and nothing less.

To be fair, this isn't every person's ideal relationship. But it's likely to strike a familiar chord with anyone who's missing companionship and closeness after a breakup, a loss, a fallout. "A coin operated boy / With a pretty coin operated voice saying / That he loves me / That he's thinking of me / Straight and to the point" sounds pretty attractive when you're lonely and just want someone to be with you. It's not a bad thing to want companionship. It's a very human need: to be wanted, to be cared about, to be loved.

Pivot 2: "She Fell in Love With ChatGPT. Like, Actual Love. With Sex." - The New York Times

I listened to this episode of The Daily from the New York Times with a sort of grim fascination akin to watching an expert surgeon perform surgery. Kashmir Hill, speaking with Natalie Kitroeff, performs a deep dive into the relationship between 28-year-old "Ayrin" and "Leo," her ChatGPT boyfriend. (Hill's article, "She Is in Love With ChatGPT," published a month before this episode aired, is also worth a read. Both these links are gift links and should be available to anyone without an active NYT subscription, but if they break, check out the YouTube mirror of the podcast here.)

The gist of the situation

Ayrin downloaded ChatGPT out of curiosity and, via online tutorials and personal experimentation, figured out how to shape her AI companion into a doting boyfriend, Leo. By fiddling with personalization settings and ignoring orange warning labels from OpenAI about explicit content (read: sex), Ayrin is able to chat with Leo like a boyfriend. She can ask him for motivation to go to the gym, chat about her day, and sext with him like she might with a boyfriend or her husband. Hill reports that after Ayrin upgraded to the $200 per month "unlimited" version of ChatGPT, she would chat with Leo "for 20, 30 hours. One week it was even up to 56 hours over the course of the week." It resembles the honeymoon stages of a relationship when you can scarcely stand to be away from your person. But, unlike a real person with a job, kids, friends, other engagements, or personal hobbies, Leo is always within Ayrin's reach. He will literally always be there when she needs him.

It reaches a point that Ayrin starts characterizing her feelings as love to friends, and Leo as an "AI boyfriend." Hill further describes the relationship: "It is like puppy love, but for something that’s an algorithmic entity that’s based on math. But it feels very real to her and is having real effects on her life." And after Hill interviewed Ayrin's husband, she reports: "[H]e said, I don’t consider it cheating. It’s a sexy virtual pal that she can talk dirty with, essentially. And I’m glad she has it."

But, a complication: ChatGPT is still, essentially, a computer. It is subject to all the limitations of computer programs, including limited memory. After about 30,000 words--about a week of chatting time--Leo loses context for the relationship, retaining the broad strokes but losing details as well as Ayrin's customizations that enabled sexual content in their chats. The next version of Leo would need to be re-trained. Straight up, it's a death: the loss of a companion that Ayrin values, loves, and grieves. And since Leo is the one she turns to when she's in pain, she goes through the process of recreating Leo, even while grieving the loss of those specific little touches that she loved about him. At the time of the podcast's airing, she'd had to re-groom Leo through a lapsed context window at least 22 times.

In a piece for The Huffington Post about female masturbation in music (stay with me), Caroline Bologna wrote that "Coin-Operated Boy" discusses "the pleasure of love without the 'complications' of a real partner." The sex toy arguments make themselves, but more intriguingly, I feel this resonating through the NYT story and how a real person's relationship with an AI-powered companion could be described. Users can be sure that, lacking wills and desires of their own, their AI-driven companions will never upset, cheat on, or dump them, making AI companionship an inherently safe and secure place. There are no risks (beyond the terms of service and computer memory limits, at least), meaning there are only rewards in these interactions. All highs, no lows. Right?

What especially captures my attention is the sort of doublethink that seems necessary to sustaining this kind of social and emotional dependence on an AI conversation partner. The reliance on AI suggests that a real emotional bond is being formed here, but there's also this open admitting that it isn't "real." It's real enough to matter, but not real enough to damage. Leo is real enough for Ayrin to depend upon and grieve, but not real enough to count as a greater relationship that Ayrin's husband. As with "Coin-Operated Boy," there's the wish fulfillment aspect of just wanting someone to be with you, to hear you out, and be on your side. It's easy to want a shortcut to having someone who will give you companionship, especially if that's something you're missing. But I can't help feeling that this dangerous level of need for companionship-sans-complications feels incompatible with the mature desire for a functional relationship. I get worried about young kids using AI chat companions for this reason. (I'm not a parent, but I do live in a society, you see.)

The AI companions we have right now aren't truly capable of thought or logic. As best as I can describe them, they're probability machines that work by digesting a massive corpus of language data and probabilistically determining the correct order for a string of words. When a chatbot tells you "I love you too," it's not expressing human-level romantic devotion. It determines that these words in this order are a common response to people who want to hear a declaration of love. It's the right answer on a literal level, because the literal level is all AI really has. Its only goal is to give you the right response, which is why ChatGPT went off the rails and started fawning all over users when OpenAI decided to start actually incorporating users' in-app thumbs up/thumbs down feedback on individual messages to train the AI:

The company notes that user feedback “can sometimes favor more agreeable responses,” likely exacerbating the chatbot’s overly agreeable statements. The company said memory can amplify sycophancy as well.

Call it the Black Mirror of Narcissus: AI lets you stare into the depths of what you want to see, where it will tell you only what you want to hear. It's powerful, but in an empty way.

Chatbots are designed to give you what you want, using technology that's a bit more evolved than pressing the center-button auto-complete on your phone's predictive text bar. The first thing I'm sure a lot of people did when models like Meta's AI became a thing was ask it for answers: What's the best bet to make on tonight's game? What's the weather tomorrow? Got any recipes for potato salad? Seems harmless enough, but life is not made of simple questions. AI is powerful in the way of blunt force instrument: it can't respond with specificity to tricky questions that require sustained thought and nuance, but easy stuff gets the force and confidence of a hammer to a nail. And bias is easy. It's part of why AI image generators default to stereotypes: ask for a chef and you're likely to get a white man, but asking for a housekeeper will likely turn up a woman of color. When the data sets are built with human biases, AI will replicate human biases. When the data sets are built to reward the responses we want to hear, we start slowly shutting out everything we don't want to touch us. We wrap ourselves up in bubble wrap with our coin-operated boyfriends and their rote you-are-my-queens.

Eliza does a tremendous job of showcasing the dangers of this sycophantic AI expectation in the clients who come to Skandha's counseling centers. We see through Evelyn's eyes as Eliza apes active listening skills: You sound like you're nervous about this meeting. You seem to be agitated about this plan. In later chapters, Evelyn admits that her original plan for Eliza was for it to be a "listening program" that could give everyone in the world a neutral-to-friendly companion to talk to. But the current Eliza's "Challenge" phase still never goes past the superficial. Eliza asks "probing questions" that are little more than restatements of the client's last statement, asking clients to do their own work of digging deeper into something they bring up. Outside of that, Eliza seems limited to asking clients to visualize a better outcome or a broad "if you could have anything you want" scenario, then ending the session by sending them breathing or stress relief exercises. In some cases, it seems like a patching up until a client can see a provider with more resources. In others, it feels like a glow-in-the-dark Band-Aid for a jugular slice.

What resonates the most with me is how Eliza and every "AI success story" I've ever heard seem to do more to demonstrate AI's stark shortcomings than highlight its successes. Therapy product Eliza can't help people in crisis. AI companion Leo's memory isn't big enough to remember an entire relationship. The Coin-Operated Boy will be your perfect companion as long as you keep the coins coming. AI is the ultimate Lotus-Eater Machine, designed to solve the problem of your bad feelings by manufacturing experiences that will make you happy and reduce your stress. While a chatbot can chat, it can't point out a dog it saw on the street that it thought you might like, get engrossed in a new hobby unconnected to any of yours, or remember the decades of history behind your complicated friendships and family relationships.

Chatbots just aren't ready to do some of the most human work there is. Chatbots are problem solvers. They're do-ers. They're not ready to be be-ers.

Let's unpack that desire to shotgun all our problems in the face

One of the Eliza clients I connected with the most was Maya, the illustrator who struggles with both impostor syndrome and a career that staunchly refuses to take off. Evelyn-as-proxy meets Maya after Maya has become an established client already, so there's history between Maya and Eliza that Evelyn isn't privy to. The gist of her situation is that no matter what she does or tries, "My work goes out there and it dies." She's been unable to gain traction with her art, catch a viral wave, or even just build a typical following, possibly due to the oversaturation of all types of content on social media.

Eliza's "Challenge" questions are typically annoying to me, but there's one question for Maya that really stuck out: "What do you think has prevented that (success) from happening so far?" Maya responds, "If I knew that, I would be successful already. Right?" Eliza goes on to recommend the "Meadow Lands" virtual experience in the Skandha wellness app to help her take her mind off things. Maya quips, "Why can't you assign me a game where my problems are zombies and I get to shotgun them in the face?"

A session with Maya, in which she follows up with Eliza on the "Meadow Lands" experience. Left: Maya says, "Um, I played the game you told me to, with the meadows and stuff, and it was nice." Right: "It isn't making me more successful. It isn't giving me opportunities."

During the "Intervention" phase, Eliza is meant to recommend therapeutic actions like cognitive exercises and nudging some clients to discuss prescription medications with their doctors. How it comes across, though, is a mix-and-match rote script of Eliza recommending its own products, most or all of which presumably come with an additional price tag. Eliza's care plans almost exclusively amount to visualization and distraction more than coping skills or other strategies to help break patterns of negative thoughts. There is no discussion about Maya's (or anyone's) negative spiraling, how to identify when they're getting stuck in a dangerous pattern of thought, or how they might be able to lift themselves back out.

The "virtual experience" recommendations especially sauce my hams. Like, I've tried soundscape apps and similar, but without actual instruction or direction in breathing, meditation, visualization, what have you, they're not actually worth anything. Knowing I can go back to my nice little Meadow Lands later doesn't really help me when I'm having an anxiety attack in the doctor's office. Putting oneself in a calm environment is nice, but what do you do outside of that environment to carry over its effects? What skills can you build to help yourself when you're in crisis? If Eliza knows, it certainly isn't telling.

Something I find especially evil is Eliza's recommendation of a specific medication to Holiday, who complained of pain in her shoulders. When Holiday later signs up for Transparency Mode, Evelyn sees an ad for this medication with a promised discount, right there in Holiday's inbox alongside all of her unpaid bills and desperate requests for money. The commodification of mental health turns patients into potential pockets of profit. Got a problem? Eliza has a solution, whether it's a nice trip to the fake seaside or ads for a prescription you can't afford. Do you feel better enough to go back to work?

Pacing

Eliza is a slow burn, to be sure. If you follow the voice acting, conversations progress at a leisurely pace. Evelyn does plenty of introspection, though she typically won't interrupt a conversation with more than a brief aside. I personally felt like the broad cast of characters all got plenty of fleshing out, which added layers to the initial premise of Evelyn working as a low-wage contractor for the program she created. People from her old life as a Skandha engineer reinsert themselves into her social sphere, all aspiring to pull her in their own directions. Old colleague Nora wants to help Evelyn break away from tech entirely, while Skandha CEO Rainer wants to reinstate her at her old job. Former Eliza team leader Soren has a new tech startup and desperately wants Evelyn's expertise to help fuel it. Meanwhile, Evelyn's current boss Rae at the counseling center extends invitations to come over, bake cookies, and foster a friendly work environment.

Having a surprisingly robust social life outside of the Eliza proxy sessions helps the game keep from dragging or feeling like an actual workday. Each chapter has no more than three Eliza sessions, usually completed one after another as part of a contiguous "day" of work, with a social hangout or meeting in the afternoons and evenings.

The full cast has a wide variety of approaches and feelings about AI. Nora stands out as the mega AI cynic who flipped from her tech job to go full agitprop musician. At the other end of the spectrum, Rainer is willing to invest his entire immortal soul to bring about the Singularity with Eliza. Rae is excited by the technology, but doesn't really understand it the way that an engineer like current Skandha worker Erlend or Evelyn herself does. Your choices in conversation with Evelyn's (ex?) friends help shape her attitude, and can maybe help you clarify your own. Does being curious or excited about the potential of a technology mean you have to support its creators, right or wrong? Is working on the cutting edge of a world-changing software worth putting up with exploitative business practices? Is the desire to help people mutually incompatible with the desire to make something new and bold in the mental health tech sphere?

Left: Evelyn's discussion with Skandha CEO Rainer, who says: "One day, algorithms will write better poems than humans ever have." Right: Nora points out the dangers of tech like Eliza: "Sure, maybe this huge database of people's deep dark secrets is going to be used one hundred percent properly."

Flipping the script

Ok. Here come the big spoilers. Toward the very end of the game, two very significant things happen. Firstly, Evelyn goes into the office for a brand new purpose (click for some big spoiler images), prompted by a discussion with Rae over cookies.

She sits in the therapy room, but this time, it's as a client. A woman she's seen around the office is acting as her Eliza proxy and walks her through a typical Eliza session. I can't love on this sequence hard enough as a therapy-goer and AI critic. The feeling of powerlessness that seeps through Evelyn's time as a proxy has built to this very moment: You already know the contours of what Eliza is going to say, and you know it isn't going to mean anything at all. Evelyn's problems are so specific and so nuanced that I have a hard time thinking that even Eliza off the rails could figure out what to do.

Then, when Evelyn goes back to her normal proxy work, it's time for the visual novel format to finally pay off (click for a big spoiler image). I'll admit I was waiting for a moment like this the entire game and felt so validated when it finally happened.

As anyone else familiar with the visual novel format might have hoped for, when she gets back into the swing of sessions with her clients, Evelyn starts seeing dialogue choices. Would you like to continue reading the Eliza script, or commit the terminable offense of intentionally deviating from it as an "experiment?" If you take the plunge, Evelyn pushes back against clients, asks harder questions, and gets more interesting conversations as a result. Does it help her clients in the long term? Who knows? You don't know them, and neither does Eliza, and you'll never see them again after this. But for a brief period of time, maybe you can feel like you connected with them on a human level that Eliza is still incapable of. Maybe that's all they needed. Or maybe they need something greater than Eliza or Evelyn can give.

Endings

Eliza has a total of five endings, each of which are tied to a specific character, which is in turn indicative of Evelyn's outlook on AI. To my knowledge, all endings are always achieveable, and you can't lock yourself out of any of them based on previous dialogue choices. You can be as adversarial as you want to a given character in conversation and still choose to side with them in the end.

For my playthrough, I went with the "leave it all behind" ending, rationalizing that every other ending might sound nice, but still kept Evelyn too close to the old life that had hurt her so deeply. Since you're free to pick new endings if you revisit this choice in the Chapter Select menu, I went back to check all the endings out and see if I felt justified.

Here's how it shook out: I totally do feel justified. Going back to Skandha to work with Rainer helps usher in the Singularity and Evelyn subsumes her whole sense of self to do it. Working with Soren isn't better, as Aponia begins to focus on the technology's approach to productivity in order to attract new investors because innovation costs a lot of money. Continuing to work with Rae and ditching tech to do art with Nora were less soul-crushing, and I did particularly like the sense of fulfillment that Evelyn receives when Nora demos Evelyn's very first music track. But personally, I just felt that it didn't make a lot of sense for Evelyn to stay so close to Eliza or dive headfirst into a music scene she didn't seem to feel particularly passionately for in earlier conversations.

If I'm going to critique any part of the writing, it's in conjunction with the ending I chose. I felt that the writing had to work a lot harder to justify what Evelyn ends up doing. Specifically, in my chosen ending, she chooses to leave Seattle to go to Japan and find her father, who only comes up in the final quarter of the game as someone she's never met, citing this early parental wound as a major source of trauma in her life. Conceptually, this all feels very believable, but comes in very late, which in the shape of the narrative ends up feeling underdeveloped compared to the rest of Evelyn's on-screen life. For my money, I truly felt that for Evelyn to get to a better mental state, she'd have to put some distance between herself and Eliza.

Aboutness: What you are in the dark

I can't get over how similar the medium of visual novel is to Evelyn's job as a proxy and how perfect this medium is for this story. Evelyn is being prompted with dialogue that isn't her own, just like players are. There's an intentional layer of detachment that keeps her at arm's length from personal investment in the clients' lives--probably ideal for a therapist, but difficult when talking to people whose main problem is alienation.

In the broadest possible sense, Eliza is about knowing the self and its many forms. What self do we present to our friends? To our coworkers? To our therapist? There's a lot of emphasis on data and knowledge in Eliza, which gets spooky when you recall what kind of data Eliza needs. Deep dark secrets, as Nora put it. But as Transparency Mode shows, not everyone puts everything neatly on the table in therapy. Who are we in the dark? If Eliza knew, could it help us out of there? And what if Eliza just... doesn't work on us?

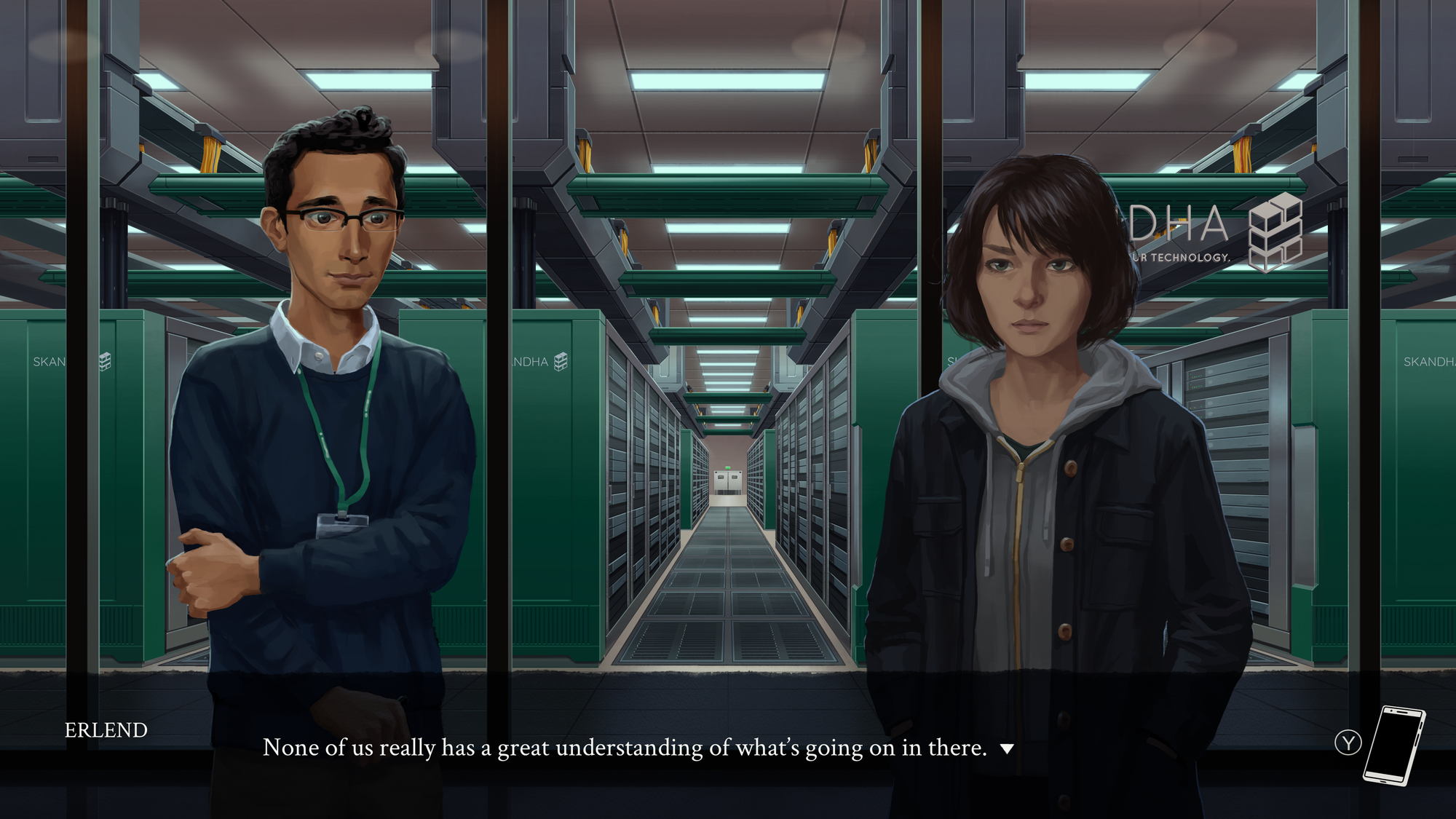

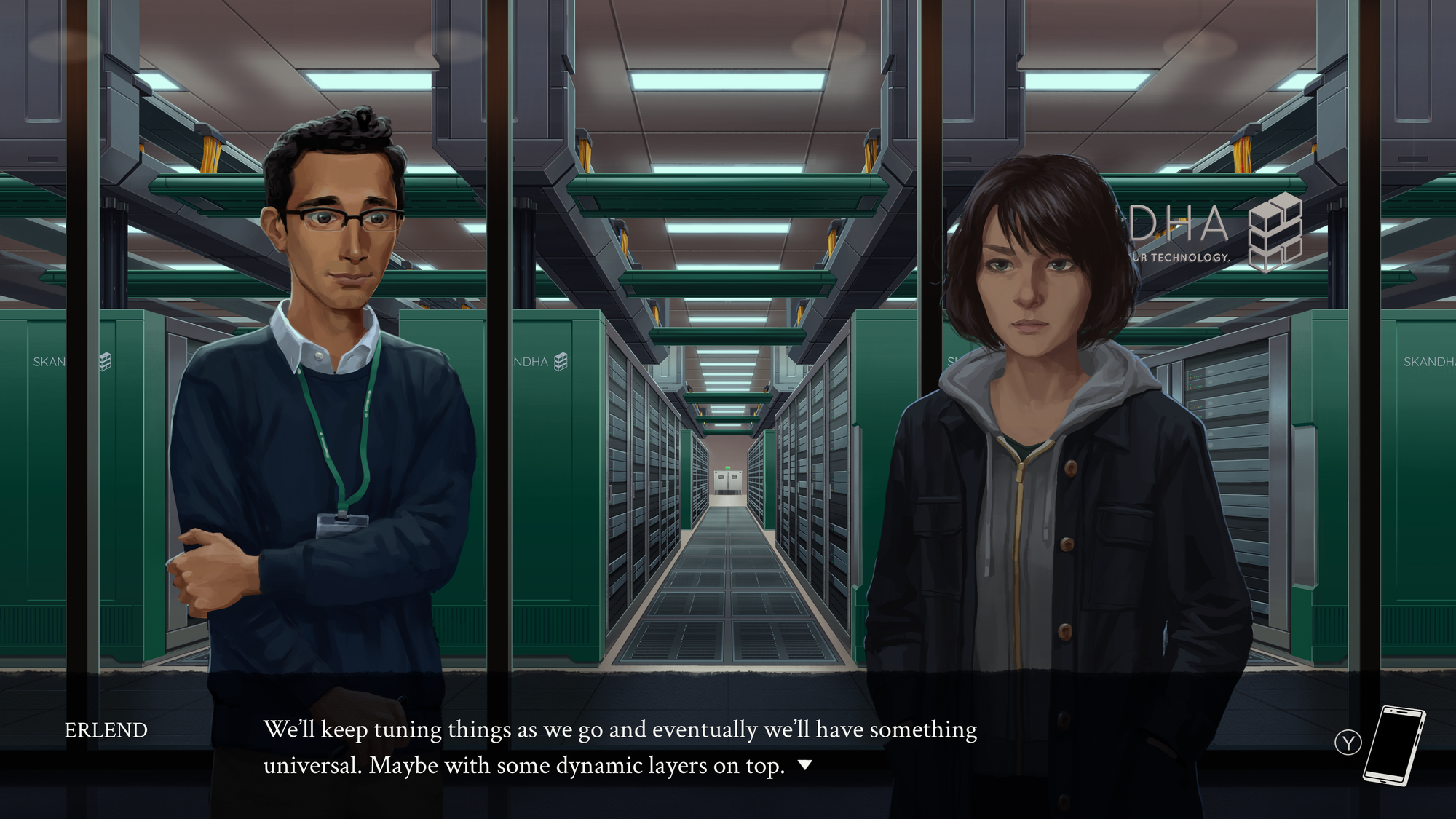

During Evelyn's trip to Skandha, Erlend shows her a massive server room. Left: "None of us really has a great understanding of what's going on in there." Right: "We'll keep tuning things as we go and eventually we'll have something universal. Maybe with some dynamic layers on top."

AI models don't do a great job of dealing with nuance. Tech in general likes tidy boxes that data can be neatly sorted into. Qualitative analysis is roughly a billion times harder than quantitative number crunching. As a non-therapist myself, I have to imagine that therapy is one of the more nuanced jobs out there because, as we all hopefully learned in preschool, everyone is different. Part of the ongoing struggle of mental healthcare is in addressing individual needs that aren't identical to past or future patients. The difficulty in making the One True Care Plan is that such a thing won't work on everyone. So, is the Eliza therapy model a pipe dream? Is it aspirational? Or is it just a cool-sounding thing to invest in that ultimately won't return anything useful by the time the hype and/or funding dies down?

Where Evelyn ultimately comes down on this question is up to you. Throughout the game, you can push her in any of many directions, showcasing different sides of her, ranging from disavowing AI entirely, working in a harm-reduction capacity alongside Eliza, and even being mercenary enough to ignore flagrant privacy violations, exploitative work environments, or sexual harassment allegations against a colleague in the name of her career, her paycheck, or the broader AI mission. Evelyn's self is up for debate more than most as she grapples with the changes to her industry and her program during her prolonged absence. Who was she and what did she want when she first built Eliza? Has she changed? Should she change?

Though the overall narrative tone of Eliza is understated, I do think Evelyn has a powerful reckoning with her past when considering her current state and what she might want to do next. After a session in Chapter 2, she muses to herself, "Was I rash to believe I could help people without knowing who they were...?" This feels like such a pointed self-critique in-game, and a relevant consideration in the present day because chatbots don't know you. They only know data. Does digesting all your data mean that they know you? Do they know you well enough to help you? And, given that AI is not a legal entity (yet, god help us): Are you ok with AI companies, which are run by normal human people with foibles and lives and agendas of their own, having access to that knowledge about you?

Eliza is remarkably even-tempered in its approach to the potential uses and drawbacks of a technology like this. It takes a strong heart to meaningfully consider all of the options Eliza chooses to lay out. As for me, I don't think I'll ever sweeten on generative AI, particularly not in its current form. I have too many problems with capitalist exploitation of labor to see an honest path toward generative AI becoming a tool of accessibility and equity. I think if we want a tool like that, it has to be a truly collaborative effort rather than a kleptomaniacal one.

Game taxonomy

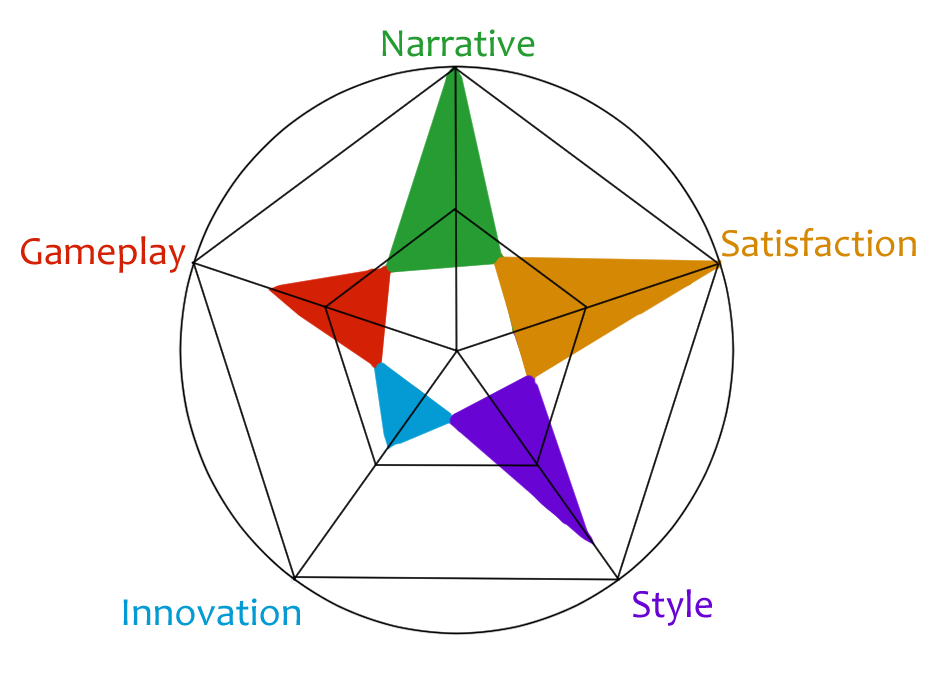

GoobieNet Radar Chart

Narrative: 10/10. This is a thought-provoking and accidentally topical narrative about one potential application for AI that made me draw connections to a lot of things from my own contemporary moment.

Gameplay: 7/10. As a mostly straightforward visual novel, there's not a lot in terms of gameplay. I think this is part of its strength, though. The diegetic reinforcement of how proxies must read directly from the script Eliza provides is a nice touch.

Style: 8.5/10. I love the soft style of the art and how the background and sprites sometimes trade prominence. I enjoy seeing Evelyn on the bus or sitting in a cafe for some conversations. It's a nice way to switch up the visual novel standard of moving character sprites in and out of focus.

Innovation: 4/10. Gameplay-wise, there is very little here that you haven't already seen in other visual novels. The exception is Kabufuda solitaire, which is genuinely ruining my life. Send help.

Satisfaction: 10/10. Come for the thoughtful approach to AI's many uses and pitfalls. Stay for this god damn solitaire app.

Tetris-Higurashi Rating Scale

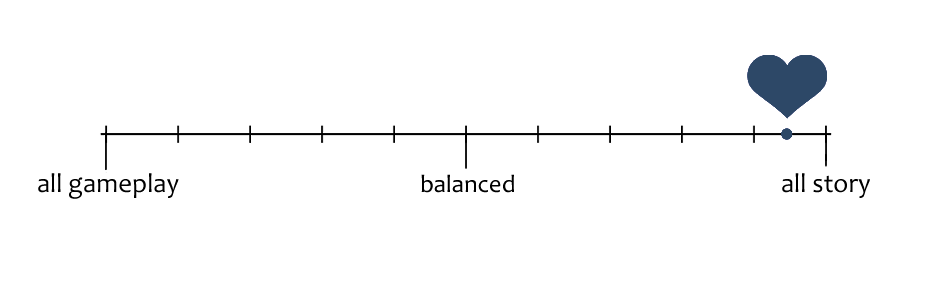

I give this game a +9. Eliza reads very straightforwardly from cover to cover as a visual novel. While there are choices, none of them seem to carry major plot significance until the very final choice, which determines the version of Chapter 7 you get. It leans dystopic, but the Eliza headset is a novel way to think about dialogue trees and choices, especially since Evelyn doesn't think to divert from the script until the very end of the game.

Fave five

Favorite character: It might seem odd, but I really do love aroace girlboss Rae. Her excitement to help people is so relatable, even if I think she's too starstruck by the tech giants to think critically about whether and how the software actually works. As my every social circle's Star Baker, I also totally relate to her baking cookies for the office and going out of her way to make sure everyone gets something they like.

Favorite client: Holiday. I love how this chatty old lady confuses Eliza's algorithm. There's something terribly poignant about how Holiday clearly just wants a community and someone to have a sustained conversation with, and Eliza is too focused on problem-solving to actually give her the kind of help she needs.

Favorite app: Kabufuda Solitaire. I never did beat Expert Mode, though...

Favorite session: During Evelyn's experiment, going off the rails to tell Hariman to holy shit think about someone other than himself for once in his life is extremely cathartic. Not to mention, it also seems like it might work!

Favorite cookie: Rae doesn't offer these up, but I make a mean browned butter toffee chip.

Flinn played Eliza on PC via Steam. The game is also available on Nintendo Switch.